In 1845 Lumberland was home to hunters, tanners, lumberjacks, timber rafters, canal related workers, as well as shoemakers, blacksmiths, wagonmakers, carpenters, and any other job necessary in a town.

The D&H Canal had brought more people to the area. By 1845, summer boarders and sportsmen started to arrive.

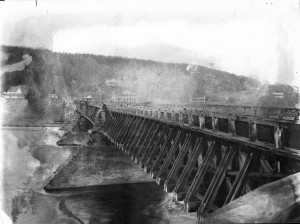

But there was a major problem at Lackawaxen, where numerous collisions often occurred between the D&H Canal traffic and the timber rafts floating down the Delaware River.

In 1847 the D&H Canal Company approved suspension designs submitted by John A. Roebling who had already built a wire suspension aqueduct at Pittsburgh in 1845.

Roebling’s designs allowed adequate space for the passage of ice floes and river traffic. (John A. Roebling, twenty years later, designed the Brooklyn Bridge.)

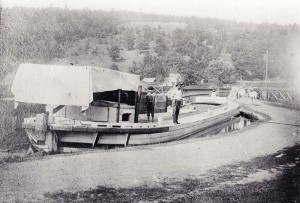

One of the four Roebling Aqueducts on the Delaware River, crossed the 535 feet from Minisink Ford, New York, to Lackawaxen, Pennsylvania.

An immediate success, the $41,750 Delaware Aqueduct and the $18,650 Lackawaxen Aqueduct reduced canal travel time by one full day, saving thousands of dollars annually.

Roebling Bridge Collection with more links

1998 Roebling Bridge