In October 1869 Julia, Abby, and Zephina—the three remaining Smith sisters—received a second unexpected tax bill, which they paid. Since women could not vote, they had no way to dispute the second bill.

To the suffrage meeting we went…—Julia E. Smith, 1876.

The Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association

October 28, 1869 was “a raw, sour day.” But the snow on the ground did not stop Julia and Abby Smith from traveling the seven miles to Hartford for the first Connecticut Woman Suffrage meeting.

The event was organized by Isabella Beecher Hooker and Frances Ellen Burr, both friends or soon-to-be-friends of Abby and Julia. The CWSA hoped to persuade the Connecticut General Assembly to ratify the Sixteenth Amendment and give Connecticut women the right to vote.

Many of the men and women who had worked towards abolishing slavery, joined the campaign to give women the right to vote. This included a number of Beecher siblings: Isabella Beecher and her husband John Hooker, Catharine E. Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe; and Rev. Henry Ward Beecher.

Girls Should Be Educated

The first session started soon after ten o’clock, in the poorly heated Roberts’ Opera House. John Hooker (direct descendant of Rev. Thomas Hooker) called the meeting to order. Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, Isabella’s half brother, prayed.

Rev. Nathaniel Judson (N.J.) Burton, pastor of the Fourth Congregational Church in Hartford, began the meeting with a good-natured talk.

Then the famous Hutchinson Family sang. The family, which originally included thirteen children, had been singing since 1841 first for Abolition and later Temperance Societies.

The speeches addressed the undercurrent of beliefs from the 1600s: girls don’t need the same education as boys; the home is the place for women and girls; woman is “owned” by the man (who takes care of her) and should depend on him for food and clothing. It was going to be a tough fight.

Susan B. Anthony, who became a good friend of Julia and Abby, spoke. Miss Anthony joked about how cold it was in the building and congratulated the first Connecticut Woman’s Suffrage Convention on their platform.

“It should be demanded,” Susan said, “that every father and mother shall educate their daughters in some honorable calling.” If they could earn their own living before marriage, “the only temptation to marry may be genuine love.” Shortly after twelve, the meeting adjourned until three p.m.

Women Had Truth on Their Side

Because of bad weather Julia and Abby went home after the first session. “Capital speeches were made,” Julia wrote seven years later. We “came home believing that the women had truth on their side, but never did it once enter our heads to refuse to pay taxes…”

The sisters missed a speech, the reading of the six articles proposed for the C.W.S.A. Constitution, and Rev. Henry Ward Beecher’s speech/sermon, which “was received with hearty applause.”

Rev. Beecher pointed out the inequities of men being paid more than women. He thought colleges should include both men and women. And countered the concept that all women were subordinate to all men.

Rev. Beecher addressed the fear that if women were allowed to vote, they would be able to hold an office. He referred to the “great-browed, great-hearted Lucretia Mott.” If Lucretia was to be voted Justice of the Peace, “she would settle two-thirds of the cases without opening a law book.

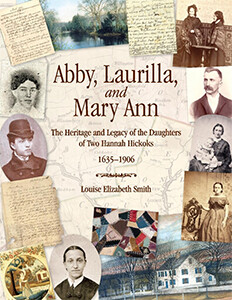

“Our government is never so safe as when it rests upon all—black or white, bond or free, male or female, native or adopted…Women…might go to Congress, but if they did, they never could be worse than men have been…”—excerpted from Abby, Laurilla, and Mary Ann, pp. 201–203.

Sources:

• Julia E. Smith, Abby Smith and Her Cows, “Introduction.”

• Frances E. Burr, History of Woman Suffrage, v.3, 321–3; “History of Connecticut Woman Suffrage,” 316–338.

• “Woman’s Suffrage Convention, First Day, Morning Session,” The Hartford Daily Courant, October 29, 1869.

• Hutchinsons: wikipedia.org.