Earlier in the year the West Africans had been taken captive by fellow Africans and forced to make the trek to the infamous Slave citadel Lomboko, on the West African coast. They were compelled to board the Slave ship Tecora to take the nightmarish Middle Passage to Cuba, a Spanish Colony.

In Cuba, knowing it was illegal, slave traders Ruiz and Montez purchased the fifty-four surviving captive Africans. (Illegal since 1820, selling Africans continued because Spanish authorities received ten dollars for each person sold into slavery.) Ruiz and Montez forced the group to board la Amistad, at the Havana Port. From there they were to be transported to another Cuban port to become Slaves on a plantation.

But on July 2, 1839 the Captives, led by Joseph Cinque* (a kidnapped rice farmer of the Mende people), escaped their shackles, killed the Captain and the cook, and seized control of la Amistad. The freed Africans pressured Ruiz and Montez to sail the schooner to Africa, which the slave traders did during the day. But at night they guided the two-masted vessel towards the American coast.

In late August 1839 the Amistad arrived on the east side of Long Island, New York. The ship was captured. Those on board were taken captive to Connecticut because that state had not yet freed Slaves.

The Amistad Case

On board la Amistad were forty-five Africans (including three girls and one boy) and the two Spanish slave traders. Ruiz and Montez claimed the Africans were their Slaves, and accused them of piracy and murder.

Abolitionists (including Arthur Tappan and his brother Lewis) became involved and made major efforts to raise funds. Roger Sherman Baldwin (grandson of Roger Sherman, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence) helped to defend the group in court against the American President Martin Van Buren, the Spanish government, and Ruiz and Montez.

The Africans were imprisoned in New Haven for eighteen months—the time it took for three court cases.

It is possible that at least Julia Smith attended the first two court cases. Julia wrote that she and her sisters visited the Amistad Africans in New Haven, and later in Farmington.

In January 1840 the District Court of Connecticut said the Amistad Africans were legally free. But President Van Buren, pressured by Spain, concerned about southern voters and his re-election, ordered the U.S. Attorney to appeal the case to the U.S. Circuit Court.

Still it was 1841 before the case was decided. In 1841 former President John Quincy Adams (the Massachusetts representative to the U.S. Congress) joined the case of United States versus The Amistad and represented the Africans in the U.S. Supreme Court. Adams believed, “By the laws of nature and nature’s God, man cannot be the property of man.”

When John Quincy Adams spoke on February 24, he first reminded the court that it was a part of the Judicial Branch and not part of the Executive.

Then Mr. Adams criticized President Martin Van Buren for assuming unconstitutional powers in the case and favoring the return of the captives to Ruiz and Montez. Adams argued that the United States should treat as free any persons escaping from illegal bondage.

On March 9, 1841, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Africans free, and authorized them to return to their homeland.

After being freed, the thirty-six Amistad survivors (six died while in New Haven) were housed in Farmington, a hub of the Underground Railroad. The Abolitionists provided housing, schooling, and help to raise funds so the group could sail back to western Africa.

The process of raising funds took a long time. The Africans longed to return home where it wasn’t cold.

Finally, on November 27, 1841, after eight months in Farmington, several American missionaries and thirty-five Africans (one person committed suicide in the Farmington Canal) boarded the Gentleman, a chartered ship, and set sail for West Africa.

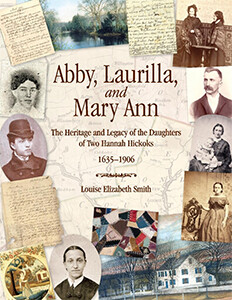

They arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in January of 1842.—Abby, Laurilla, and Mary Ann, pp. 136–139.

* The New York Sun publisher commissioned a portrait of Mr. Cinquez, as Joseph awaited trial in New Haven, Connecticut. The print was advertised for sale, when The New York Sun ran an account of the capture of La Amistad, August 31, 1839.