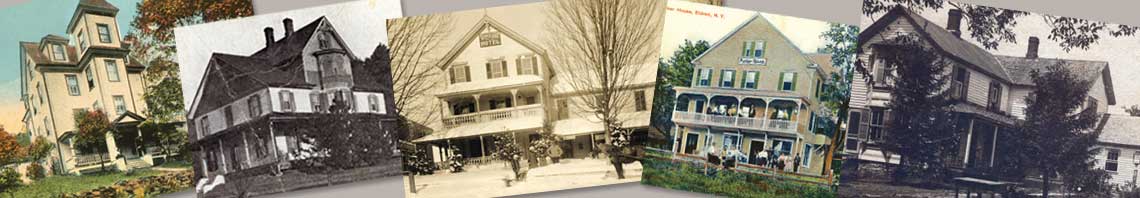

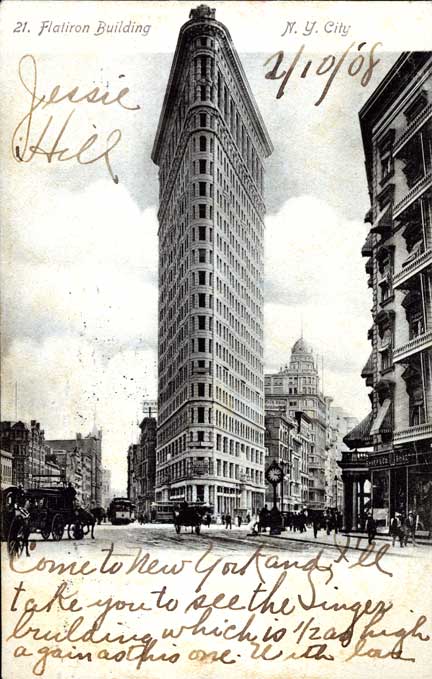

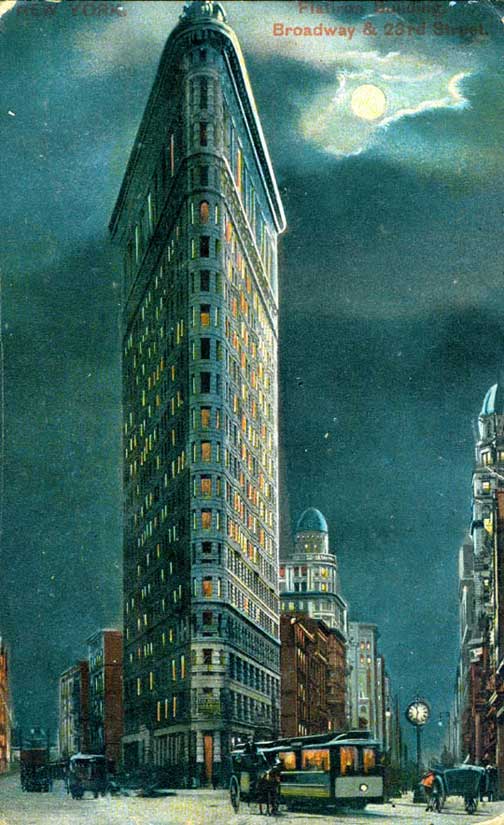

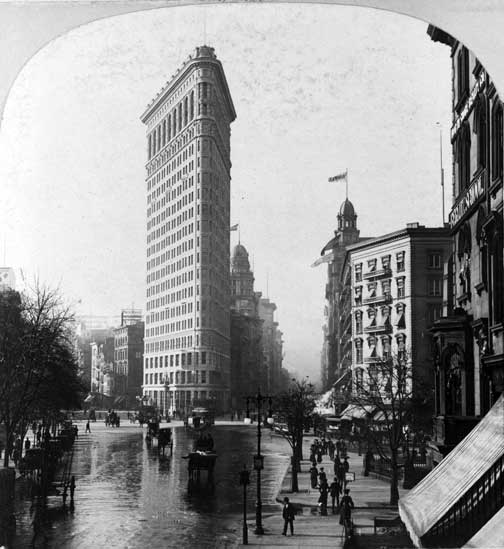

I am quite excited to share my extensive collection of postcards from the Town of Highland over the coming weeks. The 2012 post on Real Photo Postcards may be of interest as you view these many postcards.

Real Photograph Postcards

Real Photo Postcards (RPPC) seem to have started in general use in the first few years after 1900. In 1903 Kodak introduced their No. 3A Folding Pocket Camera designed for postcard-size film. The photographs could be printed on postcard backs.

Other cameras were also used to make Real Photo postcards. Some used old-fashioned glass plates that required cropping the image to fit the postcard format.

It was 1907 before the Post Office would allow a postcard to have a message written on the same side as the address.

Also, by 1907 European publishers began opening offices in the U.S. for their millions of high quality post cards. Their cards made up 75% of all postcards sold in the United States. Germany’s printing methods were the best in the world.—usps.com; wikipedia.org.