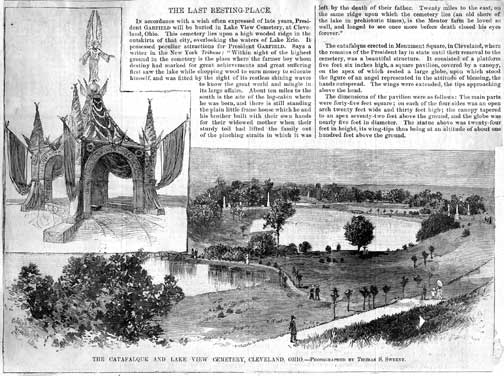

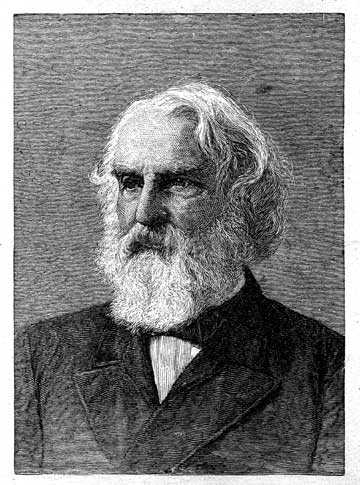

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow died March 24, 1882, at his home in

Cambridge, Massachusetts.

My dad, Art Austin, often quoted three of Mr. Longfellow’s poems: The Children’s Hour, Paul Revere’s Ride, and The Song of Hiawatha.

The following newspaper article commemorating the famous poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was in Great-Grandma Mary Ann Austin’s scrapbook. [The first verse or so of Mr. Longfellow’s last poem is included at the end.]

The unexpected death of Mr. Longfellow, following so soon upon the remarkable honors paid to him on his seventy-fifth birthday, has called forth tributes of love and sorrow from all the countries to which his fame and works have extended, and has caused a profound sensation throughout the United States and England, where his name for so many years has been a household word.

“Mad River in the White Mountains” was Longfellow’s Last Poem. This poem, on a well-known White Mountain stream, was corrected, in proof by the poet only a day or two before his death, and is now printed in the May “Atlantic.”—“The Atlantic Monthly”.

Mad River in the White Mountains

Traveller

Why dost thou wildly rush and roar,

Mad River, O Mad River?

Wilt thou not pause and cease to pour

Thy hurrying, headlong waters o’er

This rocky shelf forever?

What secret trouble stirs thy breast?

Why all this fret and flurry?

Dost thou not know that what is best

In this too restless world is rest

From over-work and worry?