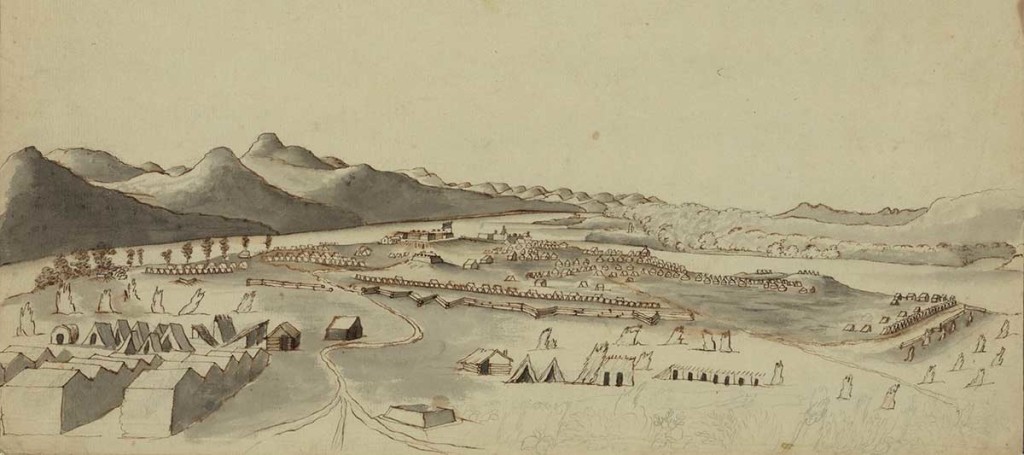

Col. Hinman versus Benedict Arnold, 1775

When he arrived at Fort Ticonderoga, Col. Benjamin Hinman used some major diplomacy in dealing with Colonel Benedict Arnold.

Benedict Arnold had joined Col. Seth Warner and Col. Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys the day before the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. Arnold demanded that he be leader. The Green Mountain Boys refused. A compromise made both Col. Allen and Col. Benedict leaders.

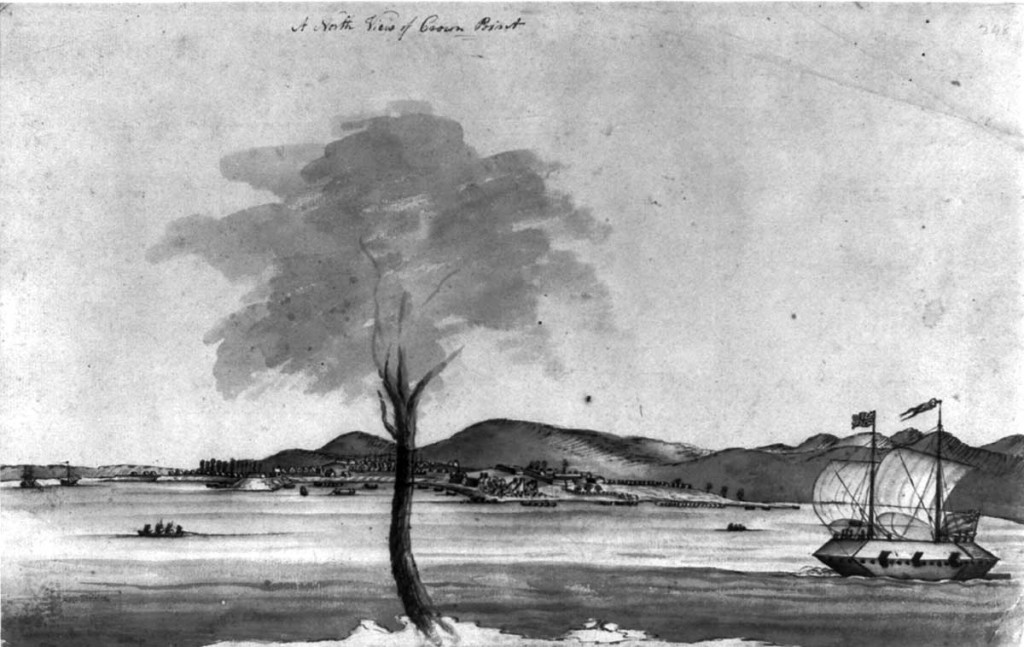

Two days after Fort Ticonderoga was taken, a detachment under Col. Seth Warner captured Fort Crown Point to the north. Col. Benedict Arnold then pronounced himself “commander-in-Chief of Crown Point.” So Allen stepped down.

Col. Arnold was in the area of Crown Point aboard a captured Sloop when Colonel Hinman arrived. Arnold would not relinquish his “command” of Crown Point to Col. Hinman. Arnold also refused Connecticut soldiers access (except upon condition) to the fort.

Col. Hinman was patient with Arnold, until a threat was made that two ships under Arnold’s command would be sailed to the British post at Saint John’s and surrendered.

Col. Hinman immediately sent a detachment to procure the ships and enlist all those of Arnold’s men who were willing. The rest were disbanded, ending the seven-day dispute over who was in command at Crown Point. Arnold’s authority was taken from him. But it did not stop him from bad mouthing the New England troops to General Schuyler when he arrived.—en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_Hinman.